Just two years earlier, Swedish troops under Wrangel’s command had captured Riga after a month-long siege, securing control over the Baltic coastline. This was a decisive step in Gustavus Adolphus’s foreign policy ambition: dominion over the Baltic Sea. Sweden, then a sparsely populated and remote northern kingdom, had suddenly become a force to be reckoned with.

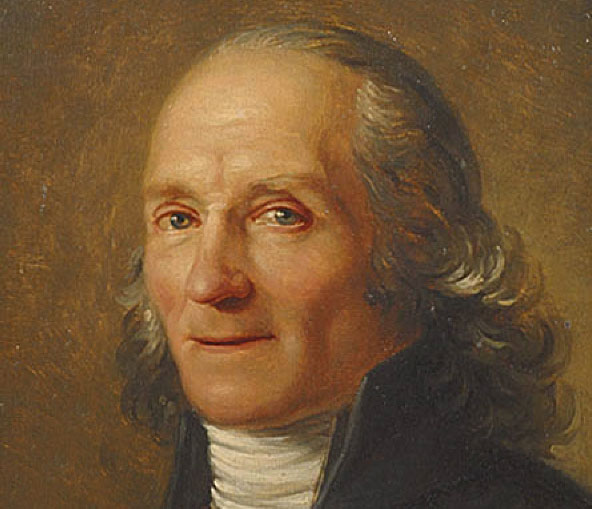

Herman Wrangel, born in Estonia in the 1580s, rose through the ranks of the Swedish army under Charles IX and Gustavus Adolphus. He fought in wars against Denmark and Russia, became Field Marshal in 1621, and was appointed Governor of Livonia. His family, of German-Baltic nobility, secured its position among Sweden’s elite through strategic marriages.

Herman Wrangel

Portrait by Georg Kräill von Bemeberg, 1626.

Under Gustavus Adolphus, the Swedish army became a model of discipline and tactical innovation. Officers from across Europe flocked to join: Germans, Balts, Scots, Englishmen, and Frenchmen. Among the most colourful characters were the Scotsman Patrick Ruthven, famed for drinking King Gustavus under the table, and David Drummond, Sweden’s first known tobacco smoker. Drummond’s grave was opened over a century after his death. His skull was found cleanly severed from his body, sparking speculation and legend.

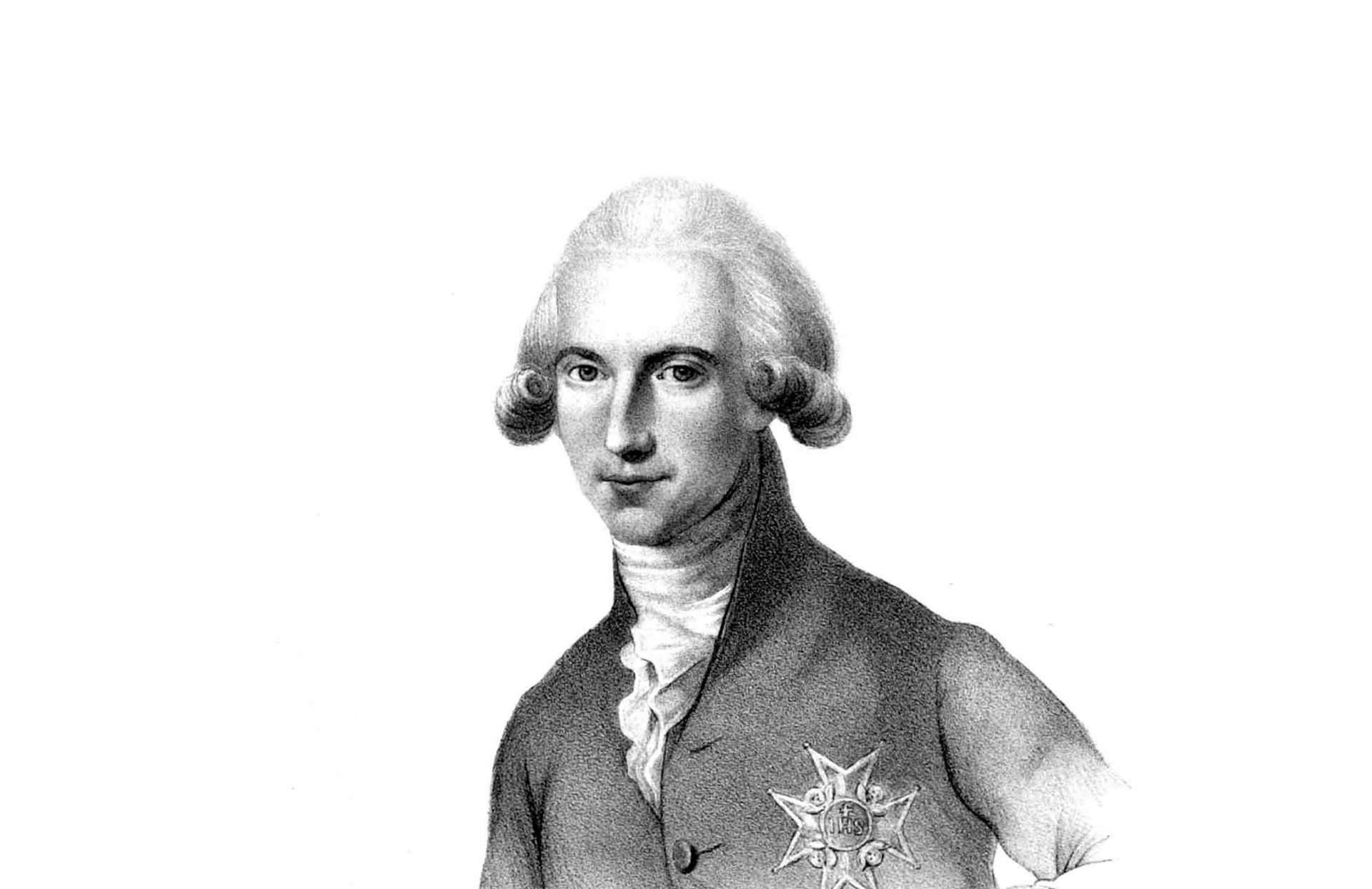

Another key figure was Georg Günther Kräill von Bemeberg, a German engineer who designed the siege plans for Riga and later became a Swedish noble. Kräill was not only a military man but also an artist. In the summer of 1623, as Kalmar faced a potential Polish invasion, he was tasked with strengthening the city’s defences. But when the enemy failed to appear, Wrangel turned from war to art, commissioning Kräill to paint his comrades.

Georg Kraill von Bemeberg

Self portrait, 1624.

Five officers were the first to pose, and soon fourteen more followed. Kräill painted twenty life-sized portraits in total – a visual record of the siege of Riga and a tribute to Wrangel’s loyal companions. These paintings were not only commemorative but also served Wrangel’s personal ambition. Lacking a sufficient number of illustrious ancestors to fill a gallery, he chose instead to immortalise his contemporaries, his fellow soldiers, servants, scholars, and friends.

The portraits were initially displayed at Kalmar Castle, where Wrangel served as governor, before being moved to the Wrangel family residence at Skokloster. In 1664, his son Carl Gustaf Wrangel relocated them to the newly built castle, where they remain to this day. Herman Wrangel’s own portrait stands at the centre, flanked by his officers, a lasting testament to the men who shaped Sweden’s imperial legacy.