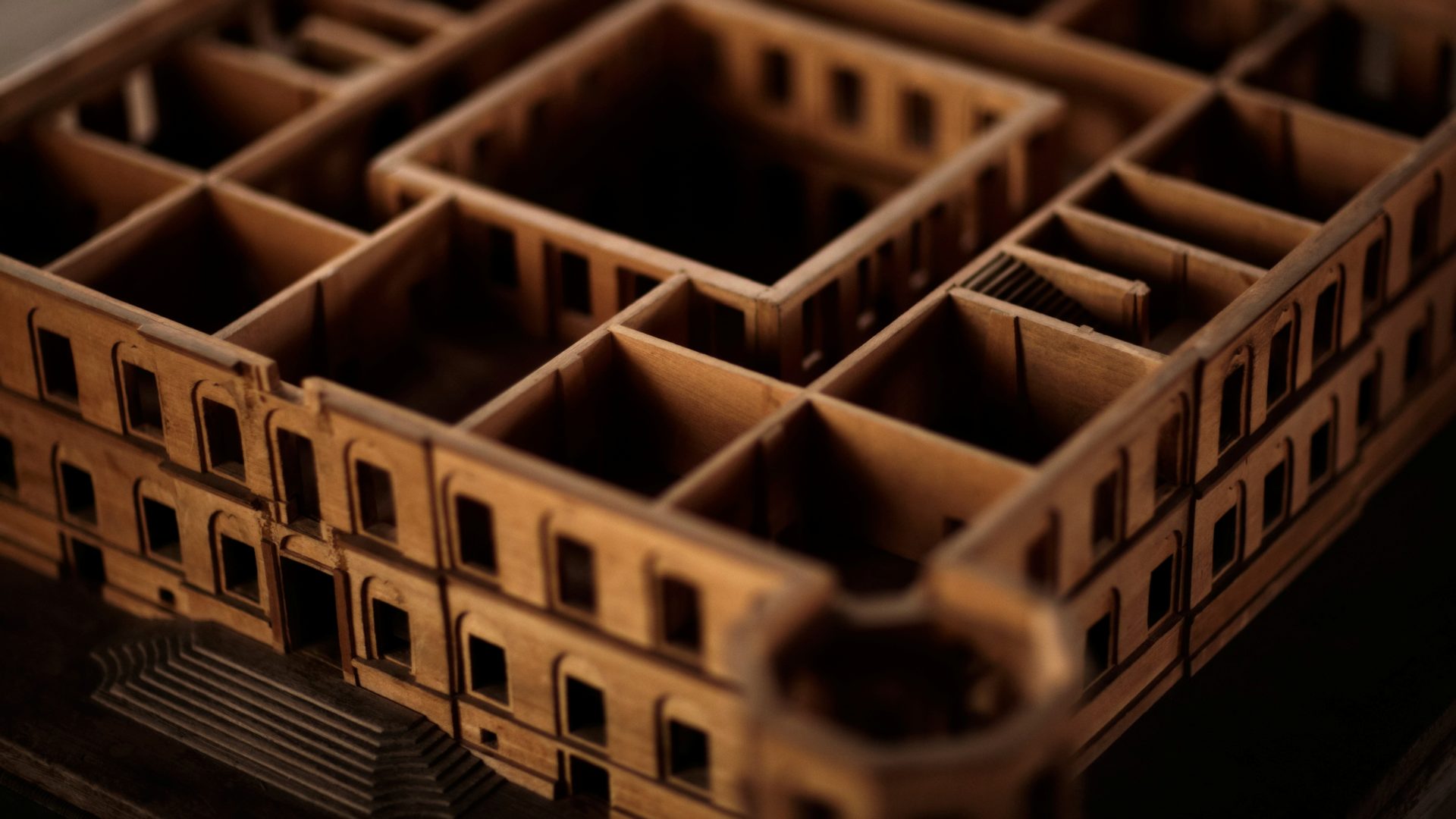

A Hellish Device

The box was once decorated with painted scrolls and ornaments. It has a handle and a few buttons. It is a time device for a time-bomb. The bomb was supposed to be used in the so-called Torstensson War of 1643-45, a part of the Thirty Years War.

The device is wound up like a clock, with a twelve hour delay. When the time is up, a small wheel turns against a piece of pyrite. The sparks created, will ignite the two powder locks and spurt out flames from the two pipes. The entire box was meant to be hidden in a larger casket containing powder, sulphur, wood-shavings, and other flammable objects.

3D-model: Erik Lernestål, Skokloster Castle/SHM (CC BY).

A Suspect

The time device was found almost by mistake. A man acting suspiciously roamed about in the harbour of Wismar in March 1645. He said that he was a cheese merchant and that his name was Hans Grefft.

The taverns he frequented were the usual watering holes for Swedish sailors and soldiers. Some of them recognised the man. He looked, they thought, very much like a man they knew was in Danish service.

The Swedish General Carl Gustaf Wrangel thought it best to apprehend the man and question him. At the same time, some soldiers were sent to Grefft’s lodgings and ransacked the room. There they found two coffins with flammable material and two time devices.

Under torture Grefft admitted that his aim was to ignite two Swedish men-of-war: the Dragon and Three Lions. It was, so Grefft said, the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand III who had given him the mission.

General Wrangel reported this to his superior Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna and took one of the time devices for his armoury.

Grefft Tells All

Grefft was discovered, interrogated, tortured and convicted. But the story does not end there. We know today that torture bring out answers, but not necessarily the true answers.

In his confession Grefft said that a tall, stout man from Lübeck had approached him roughly a month earlier. The man had worn grey, badly sewn clothes, grey hair and grey beard. His resided at The Blue Tower, owned by Jörgen Burchhart. Other accomplices were Heinrich Würger and Thomas Ritter. The latter was the leader, according to Grefft.

Of course, General Wrangel had Ritter, Burchhard and Würger arrested.

Hans Grefft was burned alive at the stake.