From Monastery to Castle

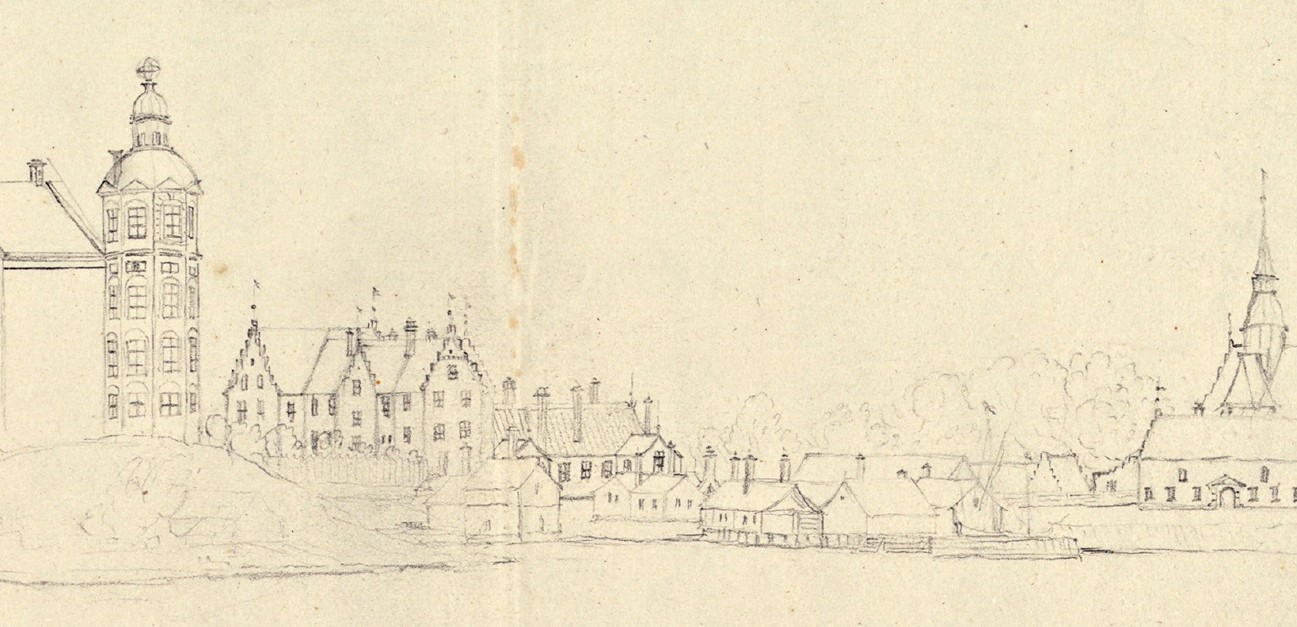

Today there is no trace left of the manor buildings that existed at Skokloster in the early 17th century. It seems that the property Herman Wrangel and his wife took over was in very poor condition. The Sko peninsula had housed a monastery since the 13th century and had a large monastery complex with adjacent buildings.

The monastery had earlier been ravaged by fire, and during the 16th century stone was taken from the monastery to Svartsjö Castle. It also lacked a proper main building. During the1610s and 1620s, Herman Wrangel and his wife Margareta Grip therefore had two old stone buildings renovated and had several wooden buildings erected to serve the needs of the estate.

They used the stone building that had formerly served as the priest’s residence as the main building. The stone building, parts of which still exist, was quite a roomy residence of three storeys with a double cross-shaped design and stepped gables.

A Proper Castle Emerges

The many battles, skirmishes and sieges that eventually came to be called the Thirty Years War laid waste a large part of Central Europe. For Sweden, on the other hand, the war represented a success. And the war made some Swedes very rich. Herman and Margareta’s son Carl Gustaf Wrangel was one of them.

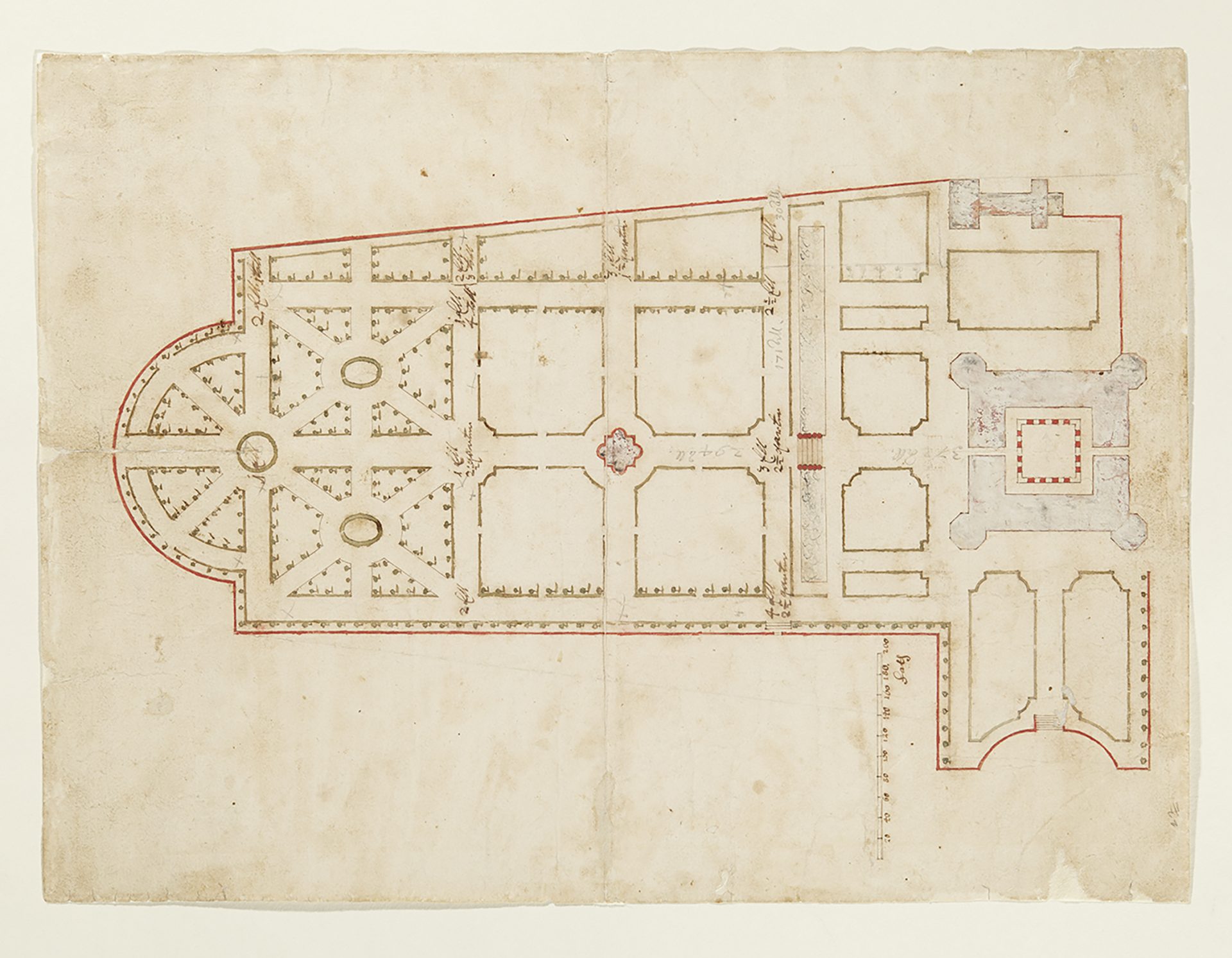

Great riches demanded a suitable lifestyle. At some time in the 1640s, therefore, Wrangel decided to make Skokloster, his birthplace, the family seat for future generations. It was to be a magnificent building, surrounded by an equally magnificent park.

The layout of the main building was to follow the standard of the time for architecture, based on the Italian architect Andrea Palladio’s symmetry. In 1570, Palladio had published a description of what characterised a beautiful building, in his eyes.

Following Palladio’s teaching, the basic structure of Skokloster Castle consisted of a square with a tower at each corner facing towards the four cardinal points. Each storey is strictly symmetrical, mirroring the northwest-southeast centre line.

The castle has four main storeys. The ground floor contained both space for servants and a small suite of rooms for the master and mistress for winter use. The first floor, called the piano nobile, was to be used for entertaining and therefore called for particular splendour.

The second floor was intended for guests and parties. A long row of guest rooms on three sides of the castle was to be linked together by a very large banqueting hall. The third floor was intended for various collections, such as an armoury and a library, as well as smaller rooms for various purposes.

An Unfulfilled Dream

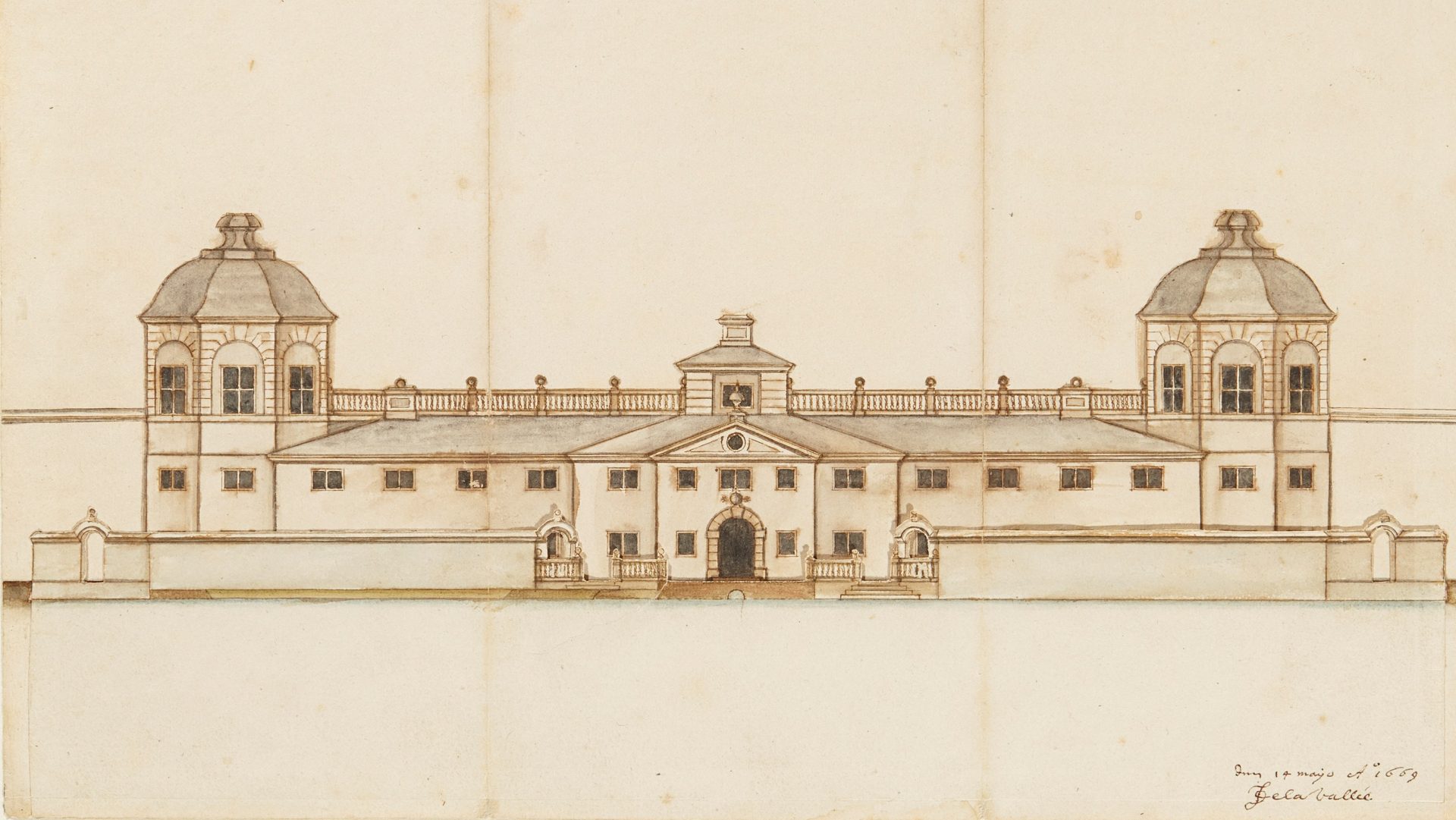

The basic design for Skokloster Castle was prepared by the Pomeranian master builder Caspar Vogel. Later additions were made by Jean de la Vallée, Mathias Spihler and Nicodemus Tessin the Elder.

The location of the castle by the water was natural for a 17th century person. It was easy to travel on the waterways, while the paths and roads on land were inaccessible. The water outside the castle is part of Lake Mälaren, which stretches from Stockholm via Sigtuna up to Uppsala.

During the 1640s, building material had already been carried by barge to Skokloster. This was mainly granite, bricks, sandstone and limestone for the shell of the building. The foundations were begun in January 1654 with the aid of Dalecarlians to do the heavy work.

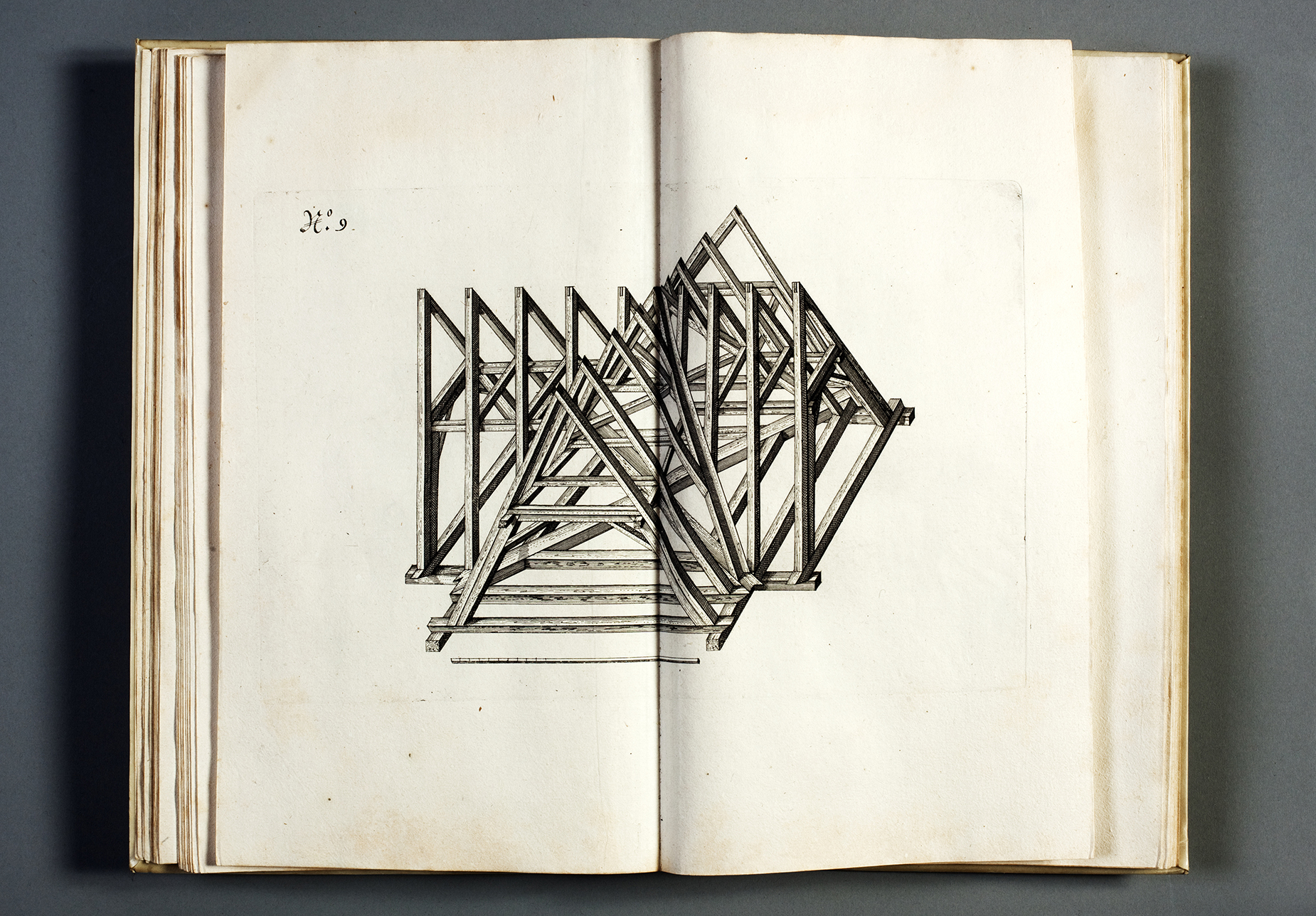

The roof is made of thick Hälsingland pine. The underside of the castle’s roof tiles can be glimpsed between the roof trusses, lying directly on laths without any inner roofing or felt. The window glass for the castle was originally ordered from Pomerania, because it was half as expensive as buying it in Stockholm.

The bricks used to build the castle are mainly local. Mälaren Valley clay was of good quality. The lime was mainly bought from Gotland. Lime was necessary for building the castle. It was mixed with sand and water and used as mortar for the brick walls.

The ready-mixed lime mortar was carried up to the walls on hods. This was hard, heavy work that was mainly done by women. At one time during building, the men working on it went on strike when they discovered that the women hod carriers were better paid than they were.

The first stage of building comprised the eastern, lakeside part of the castle. We can follow the building process closely, thanks to the regular exchange of letters between Wrangel and the castle’s building foreman Hindrich Anundsson. The exterior of the castle was finished in 1668, after which the work focused on the interiors.

The Castle that was Never Finished

Skokloster Castle was never quite finished in Wrangel’s time. When he died in 1676, large parts of the main building’s interior were incomplete and unfurnished, even though the building work had been going on for about twenty years.

There were many reasons for this long drawn-out period of construction: a shortage of qualified workers because of long periods of war, a lack of money because of the astronomical costs of Wrangel’s other properties and Wrangel’s absence. In spite of this, he ordered drawings of his dreams.

And some of the aspects that make Skokloster Castle so interesting are that the collections contain many books that inspired Wrangel, many drawings and drafts, an architect’s model of the house, some of the tools that built it and – last but definitely not least – an uncompleted banqueting hall.

After Wrangel’s Time

During the 18th century, a number of changes to the interiors were made by the Brahe family, but most of Wrangel’s adornments were saved. In the 1830s and 1840s, the castle was subject to extensive renovation on the initiative of Magnus Brahe. At the same time, he purchased many 17th century artefacts to embellish the rooms.

After the Swedish state took over Skokloster Castle in 1967, a major renovation was performed by the architect Ove Hidemark. His aim was to have the work done as carefully as possible. The work of recreating old building techniques, materials, tools and methods took ten years. This work also helped to establish a new ideological approach to restoration work in Sweden.