Skokloster Castle as a Museum

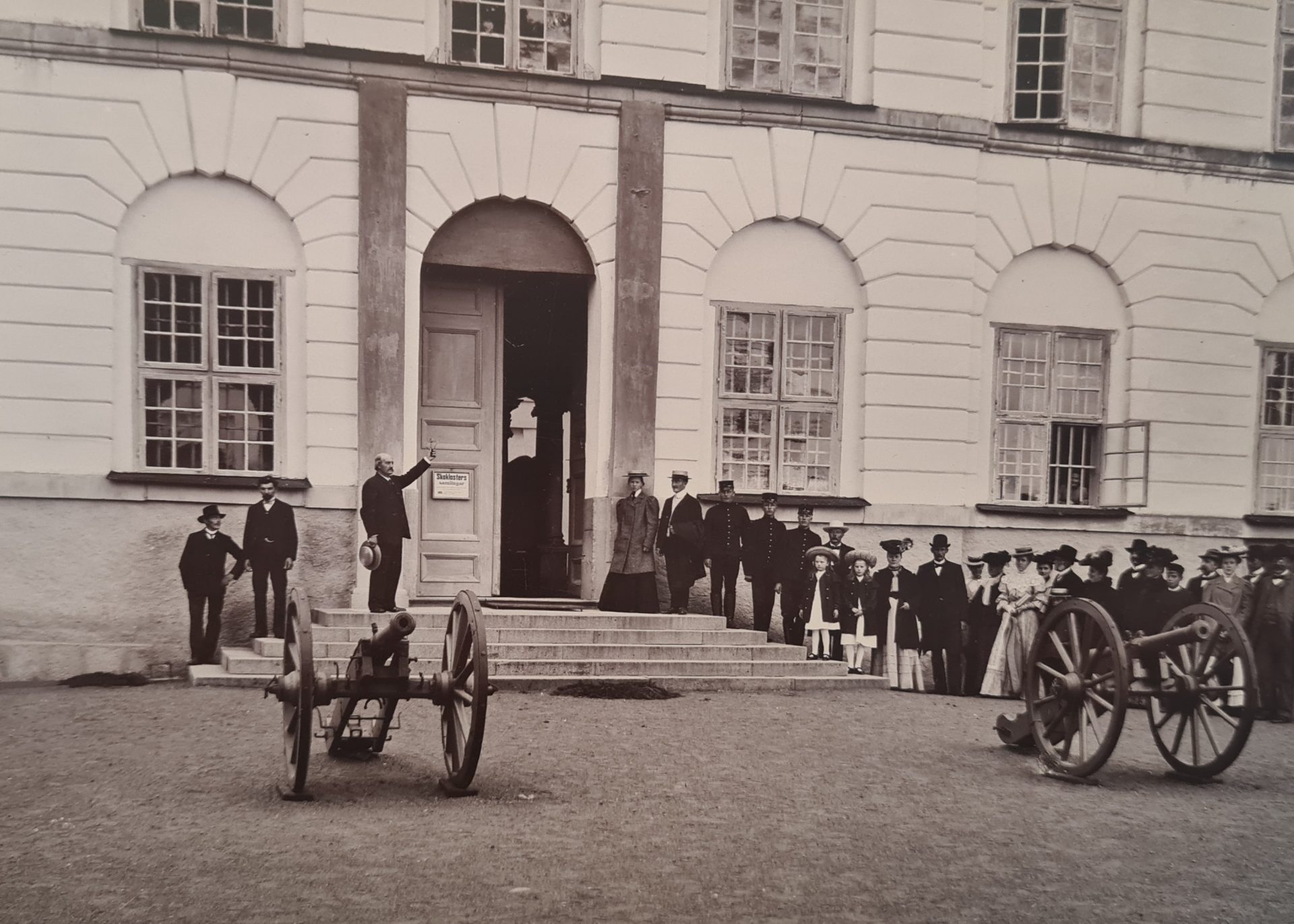

The Wrangel suite on the first floor soon became a kind of museum of his life and the period when Sweden was a great power. By the end of the 18th century, hundreds of paying visitors came to Skokloster every year to see the art treasures and to sleep in the castle’s beds.

The museum aspect was further developed in the 19th century. The passenger vessels that sailed between Uppsala and Stockholm stopped at the castle to allow visitors the opportunity to see the collections. During the inter-war years of the 1920s and 1930s, when more and more people had longer holidays and communications improved, the number of paying visitors increased. About 5,000 people visited Skokloster every year.

The armourer was a key person. His main task was to look after the weapons, armour and cannons in the armouries. The duties also included receiving visitors and showing them the castle. The master and mistress of the castle also had the support of curators who were engaged in work on the castle’s collections. One of these was Rudolf Cederström, later head of the Royal Armoury in Stockholm. He spent many summers at Skokloster studying and organising the weapon collection.

The Ladies of the Castle

During Anna Nordenfalk’s time as lady of the castle, the museum aspects were further enhanced when one of the tower rooms on the third floor became a natural history exhibition, with snail shells, stuffed birds, parts of a whale skeleton, tortoise shells and archaeological material.

The next lady of the castle, Wera von Essen, devoted a lot of time to organising and preserving the castle’s collections. She was helped in organising the collections by the curators Rudolf Cederström and Åke Stavenow.

Organising the furnishing of the rooms was an extensive project that went on for several years. The changes affected the furnishings in large parts of the castle, both those that were accessible to visitors and the private quarters. The aim was for the rooms to be “both more beautiful and to appear more natural and living”. The refurbishment was most evident in the guest room floor, two staircases up in the castle.

The guest rooms were remodelled so as to become a chronological display of the art of interiors, from the 16th century to the 19th century. Through the paintings, furnishings and other artefacts arranged according to different eras, those who visited the castle could wander through time as they went from room to room.

A tower room in the Wrangel suite was fitted out in 1935 as a museum for all the gold, silver, ivory and glass works of art. The display cabinets were designed by the armourer Emil Nyman to both display and protect the artefacts. The room’s interior was one of the few more modern designs in the castle and was part of Wera von Essen’s efforts to make the collections more accessible.

The State Takes Over

By the 1960s, it was evident that Skokloster Castle was in need of extensive repairs. The owner, Rutger von Essen, wanted to sell items from the collections to pay for the repairs. But to sell items from the entailed estate, he had to get the government’s approval. At the same time, the law on entailed estates was under review, and the outcome was that the entailed estate should be abolished.

The Swedish government took Rutger von Essen’s query about selling artefacts as a pretext to begin negotiations on the castle and the collections. In this way, the entailed estate could be abolished and the collections could become state property. After a few years of negotiations, in 1967 the state was able to acquire the castle and the collections for the sum of 25 million kronor. This amount followed from index linking the value stated in the 1936 estate inventory after the death of Rutger von Essen’s father.

Immediately after the takeover, extensive renovation of the castle began, led by the architect Ove Hidemark. At the same time, the collections were catalogued in a database, the first large-scale museum database in Sweden.

In 1978, Skokloster Castle was incorporated into a museum authority, LSH, together with the Royal Armoury and Hallwyl Museum. This coincided with a change of management at the three museums. The former head of the Royal Armoury then became the authority’s superintendent. In 2018, LSH was merged with the government agency National Historical Museums.