A Dissatisfied Young Man

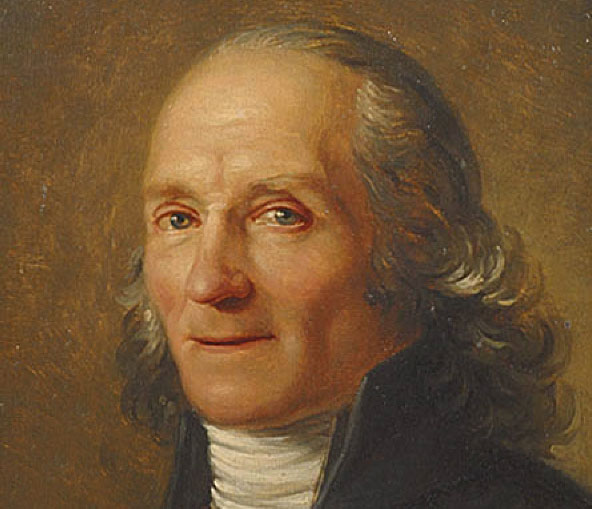

Johan Gabriel Oxenstierna

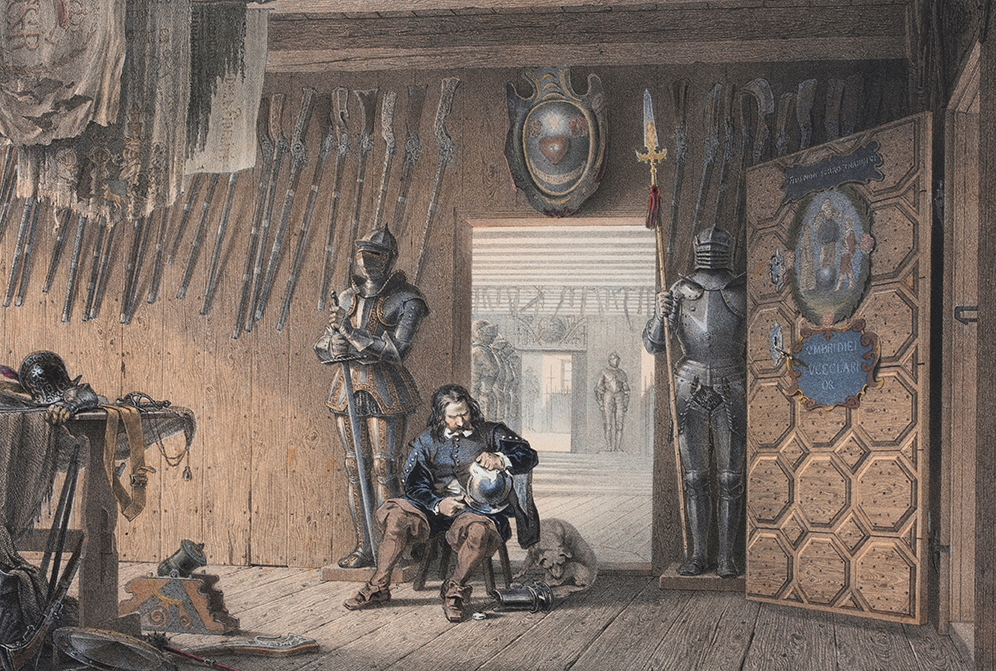

When I arrived at Skokloster, I had the opportunity to satisfy my curiosity, the greatest of my passions. I was surprised at the number of things I saw. The weapon collection there is enormous […]. The library is hardly less extensive, with 18,000 volumes. Most of them are only old books, however.

They have not been organised but are in an extraordinary disorder. The masters of this castle have always had such tastes. The weapons are well maintained. People have always been employed to look after them, while the books are disregarded, covered with the dust of the centuries, and sometimes still in the chests that General Wrangel had them packed in when he got them in Germany. It appears that these chests will be their graves for eternity, or at least I know that Count Brahe, who now owns Skokloster, is not bothered about them.

I cannot miss saying a few words about two poisoned daggers that are kept there. Their waved blades are still shiny, and I think that the poison they have been smeared with preserves their shine. This cruel poison never evaporates. They are just as terrible after a thousand years as on the first day. The slightest wound that draws blood would inevitably lead to death, for which reason the man who showed them to us never let them out of his hands.

Some of the furniture has been moved to other places, but those one still sees are very impressive. Gold and silver has been squandered and the fabrics are falling to pieces under the weight of the embroidery and pearls with which they are embellished. [---] It is hardly creditable that the masters of Skokloster allow the castle to be so unmaintained and let fall into ruin what was once plundered with so much hardship in Germany. The windows are falling apart, there is grass growing on the walls, the roof can hardly protect the building from rain and when you see this you think it is more like an owl’s nest than a palace, so impressive in bygone days.

Thus pondering, and in observing the rarities we were shown, I spent a day and two nights at Skokloster. The nights were very hard. There were five of us, the two Barons von Essen, Simming, Kempe and I, in one bed in which we were dreadfully squeezed. It was impossible. I cursed General Wrangel with all my heart for not putting another bed in our room, because to judge by the rags that covered our bed, they must have been there since his time.

After the most uncomfortable of nights, we could not get anything to eat the next morning. Their Royal Highnesses had desired to inspect Skokloster and everything possible was done for them, and we got nothing. At least it was not the first time that subjects have died of hunger in order to provide for their rulers.

[---] How I would have wanted to attack the servants who carried dinner to the prince. It was then that all the enchantment of the artefacts I had just seen disappeared from my eyes. I would have given any castle in existence for a roast and preferred supper to any weapon collection in the world. [---] Count Brahe himself showed the prince all the honour that his tumbledown castle could afford, with all the grace one might expect of a man who is short-sighted, cross-eyed, ugly, stupid and even more conceited than all the others.

[---] But even more fateful things awaited us on this unhappy journey. Since we were in such a hurry to leave, ten of us in all threw ourselves into a little, flat-bottomed boat, which was so overloaded by the weight that it was only two inches above the waterline. It was terribly windy, and to pile on more misery, the man who was rowing was drunk and we had to do all we could to prevent him from falling asleep. [---] After three hours of anxiety, we finally got ashore with no worse injury than being very wet, a piece of bad luck that was undoubtedly insignificant compared with what might have awaited us. Rather than once again set out on all the troubles and pains of such an unpleasant journey I would like the castle and all the remarkable things I saw to go to hell.